China’s Plan for a Space Blockade

A quick primer on Chinese space development

Seizing and maintaining the high ground advantage is one of the oldest laws of warfare. Today, space is the high frontier of national security and the commanding heights of the game of great power strategic competition. – People’s Liberation Army Daily [translated from Mandarin]

China has extended the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) to orbit. The CCP’s economic and cultural influence has spread throughout Asia, Africa, Oceania, and South America over the last decade – heavy investments in infrastructure and social programs give the Party direct influence over much of the Eastern hemisphere. But, the Earth may not be enough. Leadership in Beijing has quietly planned to extend their sphere of influence to the entirety of the Earth-Moon system.

Officials from China’s main space contractor (CASC) have proposed an “Earth-Moon space economic zone” to be established by 2050 that could generate an annual economic value of $10 trillion. To get there, China is rapidly developing a robust, technically ambitious, and highly agile space warfighting capability that will protect its economic and political interests.

In recent years, China has launched communications satellites for Laos, Pakistan and others. They’ve offered flood and drought monitoring data to African and Asian nations, and shared their BeiDou navigation coverage in order to make countries and regions more sympathetic to the Chinese Communist Party. The Space Information Corridor, run as part of the BRI, is essentially a Space Silk Road – enabling BRI participant states to benefit from China’s space infrastructure. In return, those countries often host Chinese ground stations or at least become dependent on Chinese satellite services.

If you’re familiar with the Soviet space program, most of China’s efforts to expand operations in Earth orbit and get to the Moon first should come as no surprise. But there’s a broader plan here to own the ultimate high ground – the Lagrange points. This piece briefly outlines that plan.

Note: I took my intelligence community hat off a few years ago, so this is more of a “space war for dummies” than an analyst’s briefing.

Close to home (LEO to GEO region)

Unlike in the US (and most Western nations) where the civilian space agency and militaristic space programs are firmly separated, the China National Space Administration (CNSA) and the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) Strategic Support Force are effectively one and the same. CNSA operates with an extreme secrecy that frequently blurs the lines between science and warfighting missions. Thus it is quite challenging for engineers and analysts in the US to determine what the full intent of Chinese orbital operations can mean.

China has been operating military satellites since the mid-1970s, and much like their efforts in the manufacturing and energy industries, have increased their productive capacity by several orders of magnitude in the last five decades.

China is now ahead of the US in building multi-modal, high-delta-V spacecraft. The Shijian-17, -21, and -25 (SJ-17, SJ-21, and SJ-25) are believed to carry a large liquid propellant tank, coupled to both a large ascent engine and smaller ACS chemical thrusters, as well as a Xenon electric propulsion system. This combined chemical/electric propulsion architecture delivers expanded mission capabilities — including rapid maneuvering and a very broad range of possible orbit changes and rendezvous operations.

In 2022, SJ-21 captured China’s Compass G2 satellite and carried it ~3,000 km to a disposal orbit. To the outside observer this may appear as China cleaning up some space junk. It would be more aptly described as a “shot across the bow” – signaling that China can capture an uncooperative satellite and kill it.

Artist’s rendering of Shijian-21

In June of 2025, the SJ-25 vehicle appeared to rendezvous with SJ-21. The SJ-25 vehicle carries robotic arms to latch onto SJ-21 and replenish its fuel. Refueling capability means Chinese space vehicles can operate with more agility to perform future inspection and interaction missions – and for far longer durations compared to life-limited US assets.

Ongoing work in non-kinetic warfare from the PLA will complement the agility of China’s space assets. Jamming, spoofing, and other signal disruption capabilities could allow for a Chinese satellite to render an American asset ineffective in short order. Similar research into directed energy, such as microwave disruption and lasers, has enabled China’s vehicles to blind and permanently damage Western space sensing equipment. The SJ-21-class of space vehicles is functionally capable of fielding such weapons.

Red Moon

China plans to land on the Moon before the US, and has far more ambitious plans to build a permanent outpost on the lunar surface – the International Lunar Research Station (ILRS) in partnership with Russia. By 2035, the plan is to have a nuclear-powered base station at the lunar south pole (home to lots of ice!) and build it out over the following decade to a large-scale settlement.

Render from Chinese announcement of the ILRS and timeline into the 2040s

In contrast, NASA’s Artemis program, and the broader Moon-to-Mars effort, have continued to shrink in ambition and scope over the last few years. What started as a plan to “go back to the Moon to stay” and then go onto Mars, has been whittled down to a short stint on the lunar surface, similar to the later Apollo missions of the 1970s.

Programs like Oracle, part of AFRL’s Cislunar Highway Patrol System (CHPS) are the first dedicated US military spacecraft for cislunar space domain awareness. Its mission is to demonstrate space surveillance and object tracking far beyond GEO, filling the gap in monitoring spacecraft or debris around the Moon. There are similar efforts from DARPA and the Space Force – but none are at a scale or funding level comparable to programs led by Beijing.

China frequently presents itself as the leader of a “multipolar” space exploration effort, in contrast to what it frames as U.S.-centered initiatives like Artemis. The effectiveness of this approach is evident in the ILRS: while no major space power besides Russia has formally signed on, many countries are keeping the door open to cooperation with China’s lunar base, hedging their bets in the event China’s program becomes the clear winner.

In the US, there is an ongoing argument as to whether returning to the Moon is a worthwhile endeavor. It’s worth a reminder that the Moon is extremely visible to nearly every human being every night, forever. Do we fully comprehend what happens to the Western psyche if an adversarial presence holds domain over the massive nightlight in the sky?

Lagrange Points: the ultimate high ground

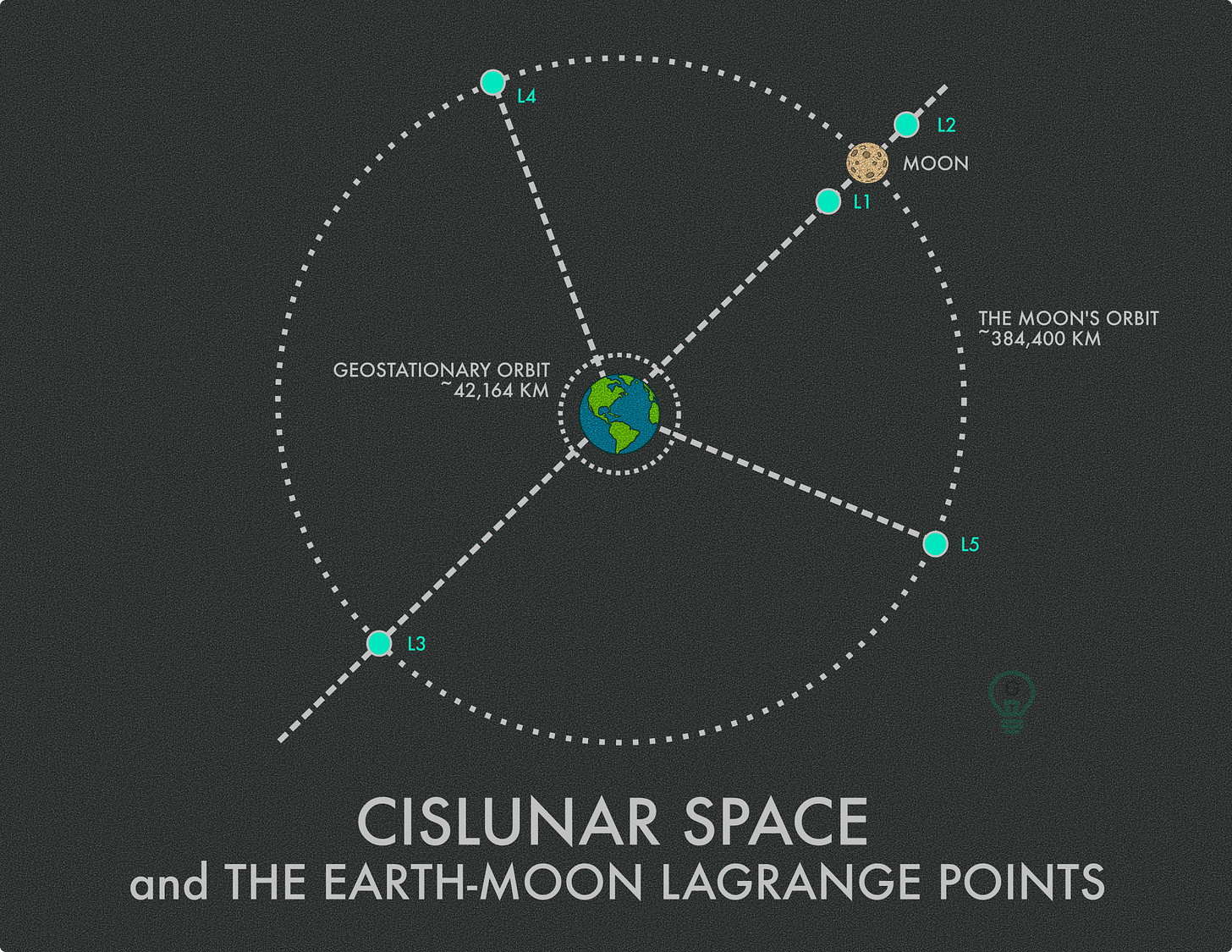

China’s space strategy focuses heavily on cislunar space – the volume of space extending beyond geostationary orbit all the way to the Moon’s orbit.

Within this region lie the Earth-Moon Lagrange points (L1 through L5), which are positions where the gravitational pulls of Earth and Moon balance out the orbital motion of a satellite. Spacecraft can “hover” in these spots (or more precisely, orbit around them in small halo orbits) with relatively little fuel. The Earth-Moon system has five Lagrange points: L1 is between Earth and the Moon; L2 is on the far side of the Moon (opposite Earth); L3 is behind the Moon on the far side of Earth; and L4 and L5 are leading and trailing the Moon in its orbit by 60° (forming an equilateral triangle with Earth and Moon). L4 and L5 are stable points where objects can persist somewhat indefinitely, whereas L1, L2, L3 are metastable and require station-keeping operations.

Satellites or space stations placed at Lagrange points are able to minimize fuel consumption, while their point of view allows for vast coverage of the Earth and Moon – for example, an infrared early-warning satellite at Earth-Moon L1 could continuously watch the Earth’s entire disk for missile launches (something one in low Earth orbit cannot do). Chinese scientists have shown interest in the idea of lunar orbiting outposts, and have noted that L4 and L5, despite being as far from the Moon as the Earth is, could allow long-term observation of the lunar far side.

Planting a flag at a Lagrange point is, in some ways, more important than on the Lunar surface. These locations offer a decisive advantage for persistent space domain awareness, intercept staging, communications chokepoints, and logistics hubs. LEO or GEO dominance alone won’t come with these strategic wins. If an entity wished to restrict access to the lunar surface (or, meaningfully control access), this is where they’d build a blockade.

China was first to place a satellite in orbit at an Earth-Moon Lagrange point. The Queqiao relay satellite, launched in 2018, was parked in a halo orbit around E-M L2 about 65,000–80,000 km above the lunar far side. From that vantage, Queqiao can see both the Moon’s far side and the Earth simultaneously, thus providing a continuous communication link. This capability was indispensable for the later Chang’e-4 mission – without Queqiao, the lander and rover on the far side would have been radio-silent behind the Moon. It effectively created a “communication outpost” beyond the Moon, something no other country has been able to replicate. China plans to maintain relay infrastructure at L2: Queqiao’s successor is expected to launch later this decade to support Chang’e-6, 7, 8 and eventually the ILRS.

While Lagrange points are unlike terrestrial high ground – in that they are themselves vast regions of empty space – there is some risk of any given actor unilaterally controlling the region, especially with a highly maneuverable or non-kinetic weapon-integrated spacecraft platform.

A clear plan to counter

Today’s Western space industry is held back by a game of chicken being played between commercial operators and state governments. China is dumping billions into securing their domain in space, while the US frequently gives out disparate contracts in the single-digit millions for critical space capabilities. Instead of racing to counter and usurp Chinese space capabilities, DoW is incorrectly focusing on platforms with “prior performance” – whose capabilities were first outmatched by our adversaries over a decade ago.

Extreme uncertainty about the future of NASA and shakeups in the Department of War have left the United States without a response or a plan for China’s growing control above our heads. America needs a clear set of goals for space superiority, and a Manhattan Project style effort that unifies technical development across the Artemis program, Department of War, and intelligence community if we are to maintain dominion in space beyond 2030.

The US currently operates several federal space programs: human spaceflight efforts (the Artemis and Commercial Crew programs + the ISS), an array of civilian science platforms (NOAA/NASA/etc.), space intelligence assets (NRO/NGA/etc.), and military assets (Air Force, Space Force). These groups operate nearly independently of each other, and frequently squabble over funding and resources. Each of them will fail at their primary mission if China’s plans for influence and infrastructure come to fruition over the next decade.

The leadership at the Department of War, the Executive Branch, and the new National Space Council, have the authority to rapidly streamline and develop a plan to ensure American leadership in space for decades to come. The US has the best engineers and technologists in the world, and an Aerospace manufacturing base primed for resurgence. We have a choice to make in the coming years whether to utilize our legacy and advantage in space – or accept that all our favorite movies are wrong and the future explorers of the solar system probably won’t speak English.

@Halen Mattison, this fits the lens I use: you can win without firing by creating repeat moments where the other side keeps paying to be careful and starts holding back. Your ground-station and service layer builds access and dependence, close-in satellite activity raises day-to-day risk in orbit, and cislunar positioning can turn “who sees first” and “who relays signals” into quiet leverage. The story is steady pressure and cost, not one big “blockade” moment.